I’m a big fan of On/Off data, which compares a team’s point differential with a player on the court versus when he’s off the court. I’ve referenced it frequently in the past and think it’s one of the more telling reflections of a player’s value to his team in the advanced stat family.

The nice part about On/Off is that it represents what actually happened. The problem with On/Off is it ignores the reasons why it happened. And sometimes, it creates a fuzzy picture because of it.

For example, let’s suppose Kobe Bryant plays the first 40 minutes of the a game and injures his ankle with the score tied at 80. LA wins the game 98-90. The Lakers were dead even when he was in the game, and +8 with him out of the game – Bryant’s on/off would be -8.

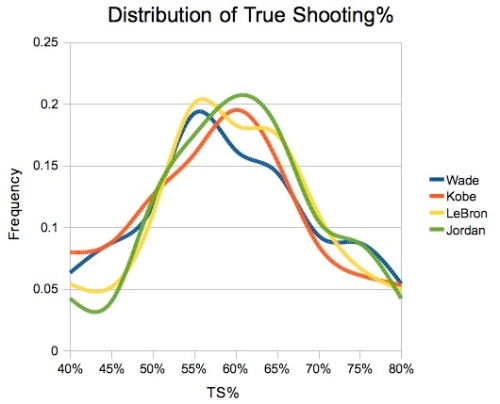

In this case, sample size is an issue. But that becomes less of a problem over the course of an entire season. The real concern is the normal variance involved in everyone else’s game. Practically speaking, it takes little outside the norm for Kobe to have played 40 brilliant minutes while his teammates missed a few open shots, and for the opponent to miss a few open shots down the stretch while Kobe’s teammates start hitting them.

The tendency is to look at a result like that and conclude that Kobe hurt his teammates’ shooting and when he left the game it helped their shooting. He very well may have by not creating good looks for them.

Then again, players hit unguarded 3-pointers about 38% of the time. Which means if the average shooter attempts five open 3-pointers, he will miss all five about 10% of the time, simply based on the probabilistic nature of shooting. A fact that has little to do with Kobe or any of the other players on the court.

In our hypothetical situation, all it takes is an 0-5 stretch from the opponent and a 3-5 stretch from LA to produce Kobe’s ugly -8 differential. The great college basketball statistician Ken Pomeroy ran some illuminating experiments on the natural variance in such numbers. His treatise is worth the read, but the gist of it is that his average player — by definition — produced a -57 on/off after 28 games (-5.7 per game) due to standard variance in a basketball game outside of that player’s control. Think about that.

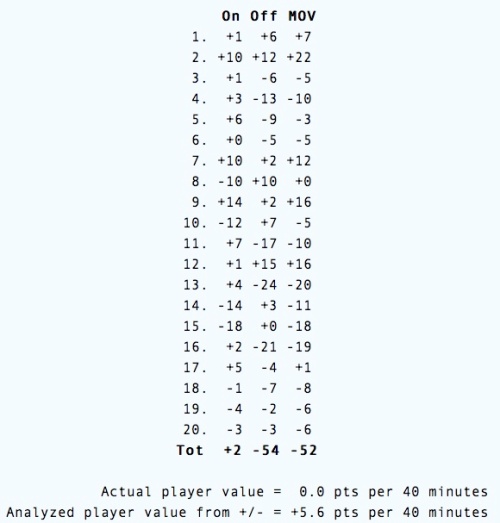

For fun, I just ran the same simulation and my average player posted a +5.6 rating of his college season:

So in two simulations, the average player’s On/Off ranged from -5.7 to +5.6. One guy looks like an All-Star, the other like an NBDL player.

“The Team Fell Apart When Player X Was Injured”

This is a common argument for MVP candidates: Look at how the team fared when he missed a few games and conclude the difference is the actual value a player provides to his team. Only this line of thinking runs into the same problems we saw above with on/off data.

Let’s take Dirk Nowitzki and this year’s Dallas Mavericks. In 62 games with Dirk, Dallas has a +4.9 differential (7.8 standard deviation). In nine games without Dirk, a -5.9 differential (7.5 standard deviation).

Which means, with a basic calculation, we can say with 95% confidence that without Nowitzki, Dallas is somewhere between a -1.0 and -10.8 differential team. Not exactly definitive, but in all likelihood they are much worse without Dirk. OK…but we can’t definitively say how much worse they are.

In a small sample, we just can’t be extremely conclusive. In this case, nine games doesn’t tell us a whole lot. New Orleans started the season 8-0…they aren’t an 82-win team.

We can perform the same thought-experiment with Dirk’s nine games that we did with Kobe’s eight minutes to display how unstable these results are. Let’s say Dallas makes three more open 3’s against Cleveland and the Cavs miss three open 3’s. What would happen to the differential numbers?

- That alone would lower the point differential two points per game.

- Our 95% confidence interval now becomes -12.1 points to +4.4 points.

That’s from adjusting just six open shots in a nine game sample.

Jason Terry — a player who benefits from playing with Dirk Nowitzki historically — had games of 3-16, 3-15 and 3-14 shooting without Dirk. He shot 39% from the floor in the nine games. By all possible accounts, Terry is better than a 39% shooter without Nowitzki. He shot 26% from 3 in those games. Let’s use his Atlanta averages instead, from when he was younger and probably not as skilled as a shooter: How would that change the way Dallas looks sans-Dirk?

Well, suddenly Terry alone provides an extra 1.7 points per game with his (still) subpar shooting. The team differential is down to -2.2 with a 95% confidence interval of -10.4 to +6.1. Just by gingerly tweaking a variable or two, the picture grows hazier and hazier.

Making Sense of it All

So, what can we say using On/Off data? It’s likely Dallas is a good deal better with Dirk Nowitzki. But, hopefully, we knew that already.

To definitely point to a small sample and say, “well this is how Dallas actually played without Dirk, so that’s his value for this year” ignores normally fluctuating variables — like Jason Terry or an open Cleveland shooter — that have little to do with Dirk Nowitzki’s value. So while such data reinforces how valuable Dirk is, we can’t say that’s how valuable he is.

We can’t ignore randomness and basic variance as part of the story.