Unless something drastic happens in the final weeks of the NBA season, Derrick Rose is going to win the MVP. He’s not a horrible choice — he’s in the top-5 on my ballot — but he’s probably not the correct choice. His supporters point to Chicago’s immense improvement from a year ago in the face of injuries to Joakim Noah and Carlos Boozer, who have missed a combined 54 games due to injury.

Only Rose isn’t responsible for a lot of that improvement.

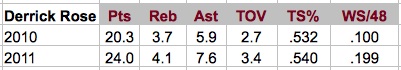

It’s been well documented that under rookie coach Tom Thibodeau, Chicago has one of the top defenses in the NBA. The Bulls have improved their offensive rating 4.3 points, from 103.5 to 107.8, and their defensive rating 5.3 points, from 105.3 to 100.0. Here’s Rose’s individual improvement from last season to this:

There’s no doubt he’s improved offensively and that has driven Chicago’s offensive improvement. Of course, the Bulls defensive improvement has been even more significant, and Rose plays a relatively small role in Chicago’s defensive dominance.

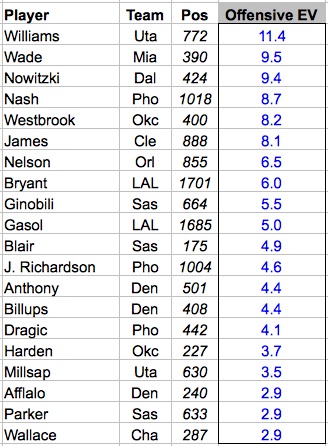

In 14 Bulls games I’ve tracked this year, the Bulls are boasting a 113.2 ORtg and 100.7 DRtg. The team breakdown is as follows:

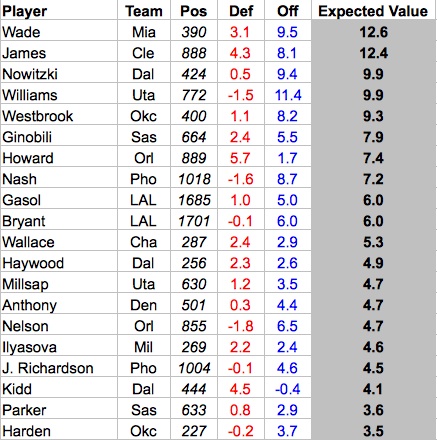

Rose’s huge EV numbers currently ranks 3rd in my database this year (although his outperforming his season averages on offense in this sample). He’s certifiably playing like a monster. His offensive load of over 54% — tops in the league — is indicative of just how much he does for Chicago on that end. He’s 2nd in Opportunities Created and 14th in assists per game, so it’s not just a shooting festival. Let’s give Rose a lot of offensive credit, but keep in mind that he’s not quite Steve Nashing* a weak offensive team, he’s Allen Iversoning* a weak offensive team. (Yes, players can be verbs too.)

*Nashing – to quarterback an otherwise weak offense to a top offense in the league. Also a superior version of “Iversoning,” which is carrying a weak offense to respectability.

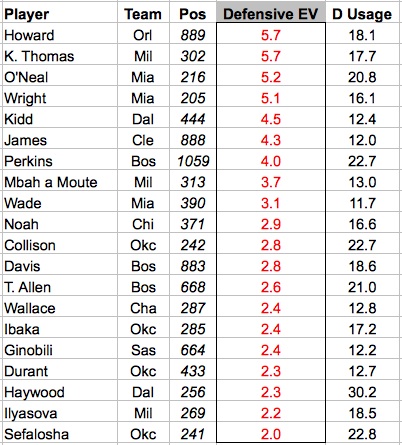

Rose is a good defender too, but he’s not largely responsible for his team’s performance on that side of the ball: Chicago’s defense with Rose on the court is 101.8. Without Rose, it’s 93.1. From the 14 games I’ve tracked, Rose has the second lowest defensive usage on the team. Not surprisingly, Chicago’s defense is powered by players like Noah, Asik, Deng and Ronnie Brewer. Just from their defense, Chicago is getting about 19 or 20 wins above .500. The offense is dead average.

(It’s also impossible to ignore the value of COY Thibs. It’s rare we can clearly point to a coach lifting a team a few SRS points, and Thibs does that with his defensive schemes. Their rotations are ridiculously tight and they are as good in that department as the historical 2008 Celtics D.)

And lost in the Bulls shuffle is the all-star level play of Luol Deng. He’s defending incredibly well, and having his best offensive season since 2007. Even Deng’s three most frequent lineups without Rose have done well.

Not surprisingly, Chicago doesn’t have a large overall point differential with and without Rose (+1.2 with him). In 826 minutes, the Bulls are a staggering +7.3 without Derrick Rose. That’s not to say he isn’t great — he is — but starting with Chicago’s impressive record and distributing credit to Rose from there is giving him equal-part credit for their team defense, and that’s just wrong.

Rose is buoying the offense from below average to average, which shouldn’t be ignored. That’s precisely the reason he is a viable MVP candidate. But for people to think Rose is the reason for a 20-win jump like we’re seeing with Chicago is a gross misapplication of credit.